Memoirs

War memoirs are interesting pieces of primary source documents. At times they contain deeply personal accounts of hardships, loss, and trauma. Other times they can reveal personal motivations and inner-thoughts related to the conflict in question. Which is why they remain some of my favorite books to read about the war. Within Soviet forces on the Eastern Front, war memoirs continue to be a complicated source for historians due to things like state censorship and party officers among troops. In most cases, Soviet soldiers were forbidden from keeping journals in case the soldier fell into enemy hands. An additional complication is that very few memoirs have been translated into other languages. Although, within the last twenty years, that trend is beginning to change, but one wonders what is lost in those translations.

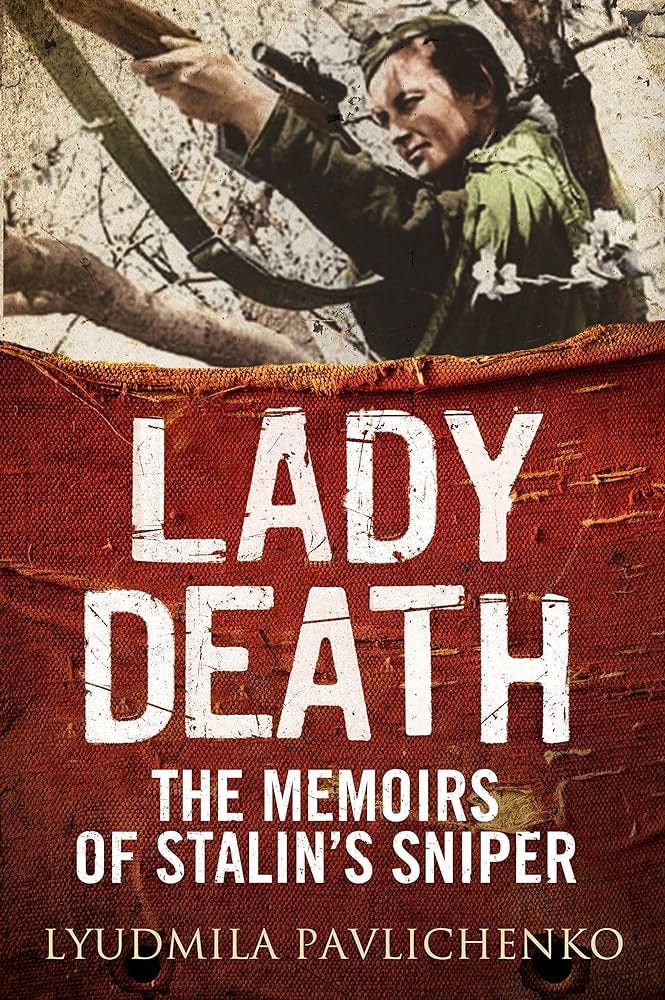

Previously mentioned, when discussing Diamond Eye by Kate Quinn, is Lady Death, Lyudmila Pavlichenko’s memoir published in 2015, with an English translation in 2018. Her book remains void of personal feelings or thoughts regarding the war beyond what was expected of her. With Pavlichenko’s death in 1974, one has to wonder how much of the text has been edited or censored in the forty-one years since.

Although rather short, one of my favorite memoirs is On the Road to Stalingrad: Memoirs of a Woman Machine Gunner by ZM Smirnova-Medvedeva, published in 1997. It details the experience of Zoya Medvedeva in the 25th Chapayev Division, her rise to company commander, and friendship (romance?) with Nina Onilova.

One of the most famous women to keep a journal and write of their time at the front was sniper Roza Shanina. Her journal is one of the few to survive the war. Shanina wrote of her desire to return to the front when she was in the rear and disparaged the attention that men paid to her. Her journal has been translated into English in 2020 under the title Stalin’s Sniper: The War Diary of Roza Shanina, but I hesitate to purchase and read the book because it’s been published independently and not done by a professional, as such, I question its quality. But, portions of Shanina’s journal can be found online.

Several airwomen have gone on to publish their accounts in the Soviet air regiments.

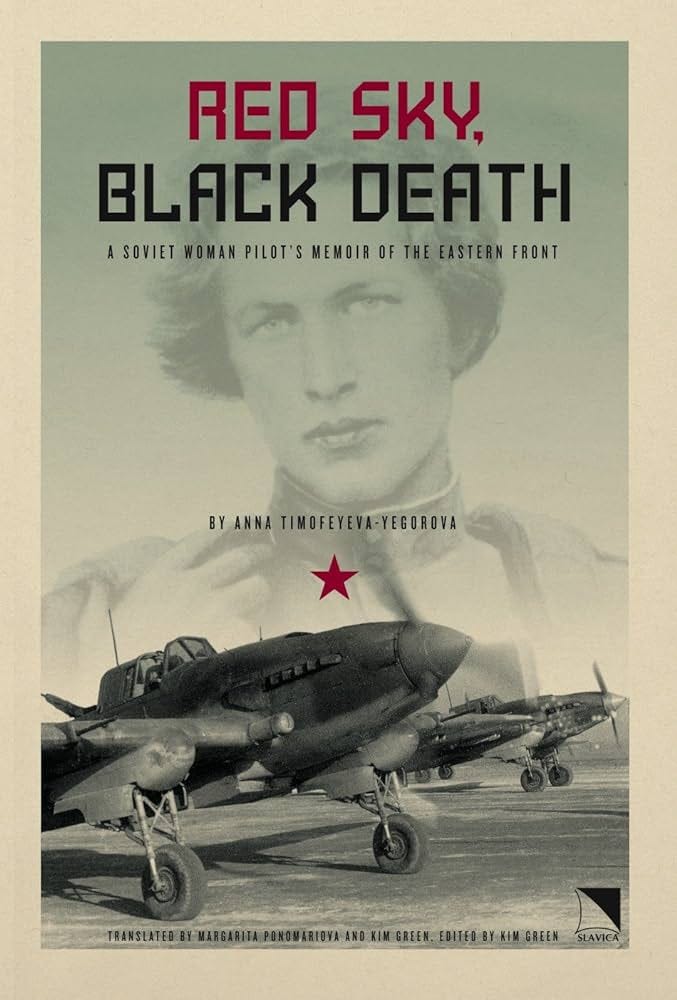

Anna Yegorova’s book Red Sky Black Death: A Soviet Woman Pilot’s Memoir of the Eastern Front, was published in English in 2009.

Yegorova was born on September 23, 1916 in northwestern Russia. After her schooling, Yegorova got a job working construction, laying rebar and tiling. In her free time, she learned flight basics at her local aeroclub. She then joined the Ulyanovsk flight school, but her brother’s political ties and arrest meant that she was expelled from the school. Yegorova then attended the Kherson flight school, where she graduated in 1939 and became an instructor for the Kalinin municipal aeroclub.

The German invasion prompted Yegorova to volunteer for the war effort. She flew a Po-2, performing delivery and reconnaissance missions for the 130th Air Liaison Squadron. After a crash, she was transferred to a training regiment, then was sent to the 805th Attack Aviation Regiment, where she flew the Ilyushin Il-2 in 41 missions over the Crimea and Poland.

On August 22, 1944 near Warsaw, her plane was hit by anti-aircraft fire, killing her gunner Yevdokiya "Dusya" Alekseyevna Nazarkina. Badly burned, Yegorova was able to exit her plane before impact, but her parachute didn’t open all the way and was wounded further upon landing. Yegorova was captured by the Wehrmacht, taken to a POW camp, and presumed dead by her comrades. On January 31, 1945 the Red Army liberated the camp near Küstrin, and Yeogorova was interrogated as a possible traitor. After eleven days, she was released and discharged from active duty service.

After the war, Yegorova married her commander, Vyacheslav Timofeev, and had two sons. In 1965, she was awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union medal. She died in Moscow on October 29, 2009.

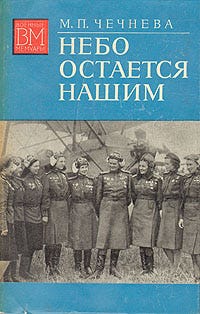

Marina Chechneva wrote several different volumes about her time during the war. some of them are Swallows Over the Front, The Sky Remains Ours, The Aircraft Take Off into the Night, Fighting Friends of Mine, and The Story of Zhenya Rudneva, all published between 1962 and 1984, none of which I have found in English.

Chechneva was born on August 15, 1922. When she turned sixteen, Chechneva learned to fly at her local flying club, wanting to become a professional pilot. After her graduation, Chechneva joined the Moscow Central Flying Club as an instructor from 1939 to 1941. After the German invasion, Chechneva volunteered for military service in October 1941. She was assigned to the 588th Night Bomber Regiment, becoming a “Night Witch.” Throughout the war Chechneva was promoted first to flight commander, then squadron commander, carrying out bombing runs in Crimea, Belarus, and Poland. It is estimated that during the war she flew 810 sorties over more than 1000 flight hours, dropped 150 tons of explosives, bombed six warehouses, 5 river crossings, four anti-aircraft emplacements, four searchlights, and a train, all while training 40 navigators and pilots. She was awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union in 1946.

After the war, Chechneva married fellow pilot, Konstantin Davydov, and had one daughter. She continued flying, setting a speed record in the Yak-18, flew in parades, was certified on the Tak-3, Yak-9, Yak-11, and Yak-18T, and was awarded the title Honoured Master of Sports of the USSR in 1951. In 1963, she graduated from the CPSU Central Committee Higher Party School and served on several committees. She died on January 21, 1984.

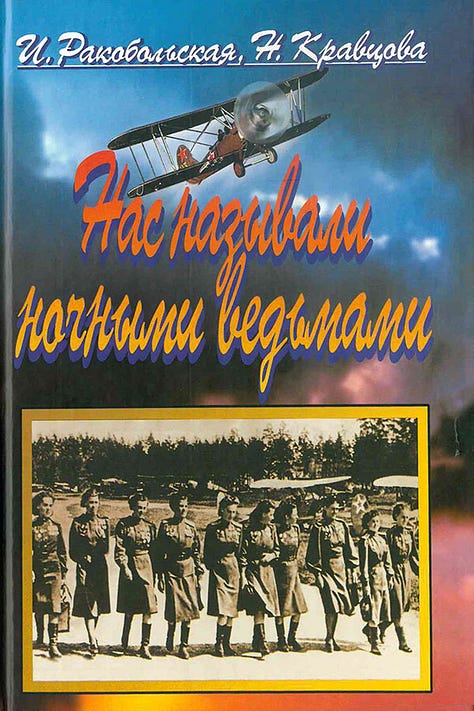

Irina Rakobolskaya wrote of her experience in We Were Called the Night Witches, authored alongside fellow airwoman, Natalya Meklin, published in 2005 (I have not been able to track down an English translation).

Irina Rakobolskaya was born on December 22, 1919, and enrolled in the Moscow State University School of Physics in 1938. Before she could finish her degree, she joined the military in October 1941 after the German invasion. Assigned to the “Night Witches” as a navigator, Rakobolskaya was soon appointed the regiment’s chief of staff in 1942. Demobilized in 1946, Rakobolskaya finished her degree and graduated in 1949. She married and had two sons.

Rakobolskaya continued her work in physics, earning her doctorate of physical and mathematical sciences in 1975, studying high energy muons in cosmic radiation. She taught physics at Moscow State University, specializing in classes on cosmic rays and nuclear physics. During her career, she published over 300 works including a textbook on nuclear physics, served on various scientific councils, and continued to lecture after retirement from the university. Rakobolskaya died on September 22, 2016.